Reviewing the New EU Environmental Crimes Directive

Last November, the European Parliament reached provisional agreement in favour of the new Environmental Crime Directive (‘the Directive’) which criminalises environmental damage ‘comparable to ecocide.’ On the 27th February, the European Parliament adopted the Directive, with 499 votes in favour, 100 against and 23 abstentions. This is a pivotal development, introducing more stringent measures against widespread environmental crime.

The Directive takes bold steps with the criminalisation of large scale environmental damage going hand in hand with increased environmental consciousness. With regard to the crime of ecocide, the Directive was weaker than hoped. Nevertheless, it takes a few steps forward in strengthening environmental protection, with a more holistic approach, new specific environmental crimes, and stricter offences, including personal liability and the the potential for extra-territorial offences. The Directive is therefore a bold transformation for the European Union in cracking down on environmental crime.

In Brief

The final compromise text of the Directive on the Protection of the Environment Through Criminal Law was released in December 2023. It followed months of negotiations between the European Council, Commission, and Parliament. The European Parliament's recommendation earlier in March 2023 solidified the commitment to creating a ‘qualified offence’ aimed at preventing and punishing the gravest environmental harms. The Directive is set to be published in Spring and will replace the existing EU Environmental Crimes Directive 2008/99/EC (‘the 2008 Directive’). Thereafter, EU member states will have two years to implement the Directive into national law.

This analysis is structured into six key segments. Firstly, it provides a brief overview of the Directive alongside the political context of the growing support for the criminalisation of ecocide. Secondly, it explores the apparent expansion and more precise definition of the environment within the Directive. Thirdly, consideration is given to the potential impact of the directive resulting from the introduction of a greater number of offences, tougher penalties, and the imposition for a higher standard of mens rea. Subsequently, it covers the preventative obligations placed on member states. Thereafter, this analysis considers the value and limitations of the harmonisation of environmental crimes in the European Union. Lastly, it turns to what this Directive means for the future of environmental protection and criminal environmental law.

The Background

The political will for a crime of ecocide is a result of years of campaigning to codify and harmonise the crime of widespread environmental damage.This was spearheaded by Polly Higgins, who co-founded Stop Ecocide International and first published a proposal for Ecocide in 2010. It was an uphill battle, difficult to get funding or support from NGOs who perceived it as too high-risk or controversial – and have been proven wrong.

It is worth noting that environmental damage is recognised as a crime by Member States per the 2008 Directive, and the Commission's report found that 38% of respondents mentioned recognition of ecocide. However, environmental harm often does not respect national borders, and national legal frameworks have proven to be limited when addressing the effects of environmental harm internationally. The intention behind the new Directive is that it will harmonise the crime of widespread environmental damage across EU Member States.

The Commission’s initial proposal to revise the Environmental Crimes Directive was made in light of the evaluation report on the 2008 Directive. The main objectives for the revision were to:

- Clarify the terms used in the definitions of environmental crime,

- Update the Directive by introducing new environmental offences under its scope,

- Define types of sanctions and the different levels of environmental crime,

- Foster harmonisation through cross-border investigation and prosecution,

- Improve informed decision-making on environmental crime through improved collection and dissemination of statistical data according to common standards in all member states,

- Improve the effectiveness of national enforcement chains.

As above, the decision follows growing political pressure to entrench and harmonise a crime of ecocide. The Independent Expert Panel (IEP) for the legal Definition of Ecocide defined it as:

“‘Ecocide’ means unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts.”

Crucially, the crime of ecocide is needed to fill a gap, as typically there is no general crime for environmental harm. Whilst there have been some mechanisms in place to address such damage, these have been scattered, loosely defined, and mostly administrative instead of having strong criminal sanctions (see eg European Commission's report on the 2008 Directive). The pressure for a stronger crime of ecocide reflects a broader societal shift towards environmental consciousness. Because we use criminal law to delineate what is morally acceptable, the criminalisation of ecocide is imperative to assert the moral transgressions associated with large-scale environmental harm. In other words, if society thinks that large-scale environmental damage is wrong, then this must be reflected and clearly defined in criminal law.

The Directive, however, does not introduce a crime of ecocide as such. Instead, careful wording creates a qualified offence which is described in the preamble as covering ‘acts comparable to ecocide.’ The careful wording is a deliberate attempt to avoid transplanting the IEP concept of ecocide. Rather, the Directive’s qualified offence is slightly narrower: ‘conduct (which) causes death or serious injury to any person or substantial damage to air, water or soil quality, or to an ecosystem, animals or plants.’ (discussed further below).

Definitions

As a starting point, we may consider the definition of the environment and thereby the extent of environmental crime. The Directive serves as a huge step towards a holistic definition of the environment. The preamble states:

"The environment should be protected in a wide sense, as set out under Article 3(3) TEU and Article 191 TFEU, covering all natural resources - air, water, soil, ecosystems, including ecosystem services and functions, wild fauna and flora including habitats, as well as services provided by natural resources."

(Preamble, (9))

This substantially expands upon the definition in the 2008 Directive which referred only to protected sites, flora and fauna. The 2008 Directive did not explicitly provide a comprehensive definition of the term ‘environment’ itself, as its primary purpose was to establish criminal sanctions for certain environmental offences. Because these crimes were quite specific and referred to the listed acts, there was no legal framework to address mass environmental damage in and of itself.

This expansion is further demonstrated by the use of the term ‘ecosystems, including ecosystem functions.’ The initial text proposed by the Commission did not make reference to ecosystems. This more holistic approach to defining the environment is a welcomed extension of the proposed definition. Pertinently, because the environment operates as an intricate network of sensitive relationships, it is vital that environmental crime considers the environmental impact of harm further down the chain of causation.

That being said, the Directive could go further in the aim of valuing nature in and of itself, irrespective of human interests. This is further evidenced by the fact that sanctions are higher where there is observable harm to human life. This demonstrates another deviation from the aim of a crime of ecocide which is to protect not only humans but the environment itself. Polly Higgins et al defined ecocide as the destruction of ecosystems to the extent that ‘peaceful enjoyment by the inhabitants of that territory has been severely diminished.’ The term ‘inhabitants’ refers to both human and non-human life, making the crime of ecocide one against all living things.

It has indeed been argued that the IEP’s legal definition of ecocide swayed too far on the side of anthropocentrism in order to make the proposal more palatable for state support. Consequently, it is conceivable that the European Union may have further diluted this concept of ecocide, codifying a qualified offence ‘comparable to ecocide’ within a framework that still predominantly centres on human interests. As such, whilst the EU’s Directive is a welcomed transformation in terms of preventing widespread environmental damage, there is more to be done in terms of realising the harm caused by ecocide irrespective of human interests.

Offences and Penalties

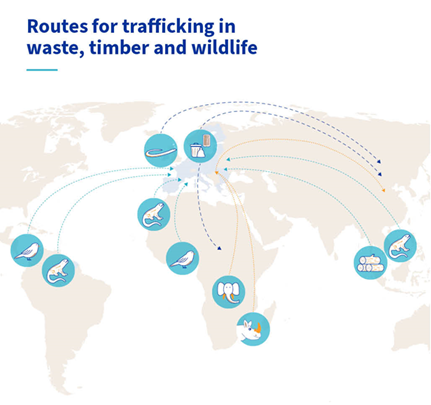

The number of criminal environmental offences will be doubled from nine to eighteen. These new offences include: illegal logging; recycling of polluting components of ships; transport and treatment of waste; introduction of invasive species; and illegal water withdrawals. The Directive is significant because it not only broadens the scope of environmental crime, but by increasing the number of offences of specific harmful conduct, it clarifies that which needs careful regulation. Furthermore, the Directive includes aggravating circumstances with respect to the offences.

Acts ‘comparable to ecocide’ constitute an offence when ‘committed intentionally and, in certain cases, also when committed with at least serious negligence.’ Unfortunately, this resulting so-called ‘qualified offence’ is weaker than many wanted. There is a significant departure from the IEP’s suggestion of recklessness as the mens rea for the crime, which is worrying, particularly in the aggravating circumstances. Though the Directive acknowledges the need to address wilful blindness, this is less prominent than in an earlier draft, which referred to ‘wanton’ acts referring to the ‘reckless disregard’ for damage.

Next, we may consider the extent of the penalties introduced by the Directive. The Directive introduces imprisonment for individuals (including company representatives). This is significant, as for those in charge of companies, this should be a much bigger deterrent than just a fine for the company. The qualified offence is punishable with up to eight years of imprisonment, or up ten if resulting in death to humans, and other offences up to five. Member states can impose fines on companies as a proportion of turnover (up to 5%) or fixed amounts up to €40 million. Additional measures may include environmental reinstatement, compensation, exclusion from public funding, or withdrawal of permits.

The scale of environmental crime attests to the fact that more needs to be done in this respect. It is evident that the 2008 Directive is not sufficiently deterring pollution. According to the World Bank, environmental crime is the fourth largest criminal activity in the world and costs over $1 trillion per year. Extending sanctions to include imprisonment can therefore be seen as a vital step forward in the legal protection against widespread environmental damage. The Directive specifies that liability for a company (or other legal person) does not preclude liability for the individual acting on behalf of the company. The recommendations made by the IEP suggest that introducing personal liability is an important development that will ‘signal the end of corporate immunity’: instead of corporations simply budgeting for the possibility of a fine, the directors themselves may be punished.

One significant improvement on the 2008 Directive is that complying with a permit no longer necessarily means there is no liability:

“When implemented by the member states, operators must be aware that merely complying with a permit no longer frees them from criminal liability. And that is no less than a revolution.”

Prof. Michael Faure, University of Maastricht (source)

The tension can be described as “how to combine the requirements of criminal law (precision, predictability) with environmental law, which operates by balancing different interests and principles.” (Bosio 2023, p54). As such, this Directive takes a more ‘criminal law’ type approach.

Pertinently, the Directive introduces penalties for legal persons across member states. Ensuring consistency across member states is key to maintaining an effective legal framework for climate justice and avoiding so-called pollution ‘hot spots.’ As such, the strengthening of penalties and the concurrent harmonisation across the European Union gives hope for a more effective and consistent legal framework which can adequately address widespread environmental damage.

Preventative Action

The Preventative Principle acts as a ‘red thread’ throughout the Directive. This is unsurprising as it is a key principle of environmental law.

The preamble stipulates:

"Judicial and administrative authorities in the Member States should have at their disposal a range of criminal penalties and sanctions and other measures, including preventive measures, to address different types of criminal behaviour in a tailored, timely, proportionate and effective manner."

(Preamble, (22))

The value of the preventative principle is that it grants legal power to take action before damage occurs. Whilst a full analysis of the principle is beyond the scope of this analysis, the imposed obligations for preventative measures against environmental harm is an important step forwards for environmental protection. Such is the case because the Directive goes further than providing legal grounds for preventative action, but also implements an obligation to foster increased social awareness on the topic as a more long-term preventative solution. Article 15 stipulates:

"Member States shall take appropriate action, such as information and awareness-raising campaigns targeting relevant stakeholders both from the public and private sector and research and education programmes, aimed at reducing overall environmental criminal offences, raising public awareness and reducing the risk of an environmental criminal offence. Where appropriate, Member States shall act in cooperation with these stakeholders."

However, the extent to which the preventative principle will be effective in realising a positive obligation to prevent environmental damage comparable to ecocide is uncertain. In part, because ‘appropriate action’ is not clearly defined and may vary considerably in interpretation. This approach has the potential to bring about significant change for environmental protection, but this will depend on whether a member state chooses to take it seriously.

Harmonisation

This brings us along to the next key aspect of the Directive, namely that of harmonisation of environmental crime across EU member states. As above, one of the main objectives of the revised Directive was to ‘Foster harmonisation through cross-border investigation and prosecution.’ Research funded by the European Union Action to Fight Environmental Crime found that:

"Further harmonisation will serve as a safeguard enhancing legal certainty and compliance with the principle of legality in criminal offences and sanctions and can serve to clarify the relationship between criminal and administrative environmental law. Further harmonisation can also address current gaps in the law, especially with regard to the criminalisation of serious forms of cross-border environmental crime and the laundering of the proceeds of environmental crime."

In light of these findings, a question we may want to ask is: how does harmonisation address gaps in the law? This Directive will bring states with less stringent measures in place up to the same standard as member states with better environmental protection. However, it may also strengthen environmental protection in member states with a relatively high level of protection. This follows from the fact that companies in ‘better’ member states opt to conduct environmentally detrimental operations in countries with a more lax interpretation of environmental crime, thereafter reaping the rewards domestically. Such activities are sometimes referred to as ‘forum shopping’ and significantly limit the usefulness of environmental protection in ‘better’ member states.

By harmonising definitions, standardising interpretation and maintaining consistent penalties, the hope would be that the EU will do away with the practice of ‘forum shopping.’ This is significant as it ensures that all companies, regardless of their size, will be subject to the same environmental standards.

The knock-on effect is the challenge that there could be more ‘forum shopping’ beyond the EU, ultimately creating pollution ‘hot spots'. The Directive seeks to address this by introducing the concept of liability for international actors in EU member states.

The Directive proposal states:

"Given, in particular, the mobility of perpetrators of illegal conduct covered by this Directive, together with the cross-border nature of offences and the possibility of crossborder investigations, Member States should establish jurisdiction in order to counter such conduct effectively."

(Preamble, (23))

Effectively, the Directive establishes that member states will have the discretion to extend jurisdiction to include offences committed outside EU borders. Member states shall inform the commission when such an extension takes place, as this is yet to be agreed upon by the EU.

Article 12(2) states that an offence under Articles 3 and 4 can take place outside its territory where:

(a) the offence is committed for the benefit of a legal person established on its territory;

(b) the offence is committed against one of its nationals or its habitual residents;

(c) the offence has created a severe risk for the environment on its territory.

The extra-territorial effects of the Directive has the potential to be a monumental step forward for the prevention of environmental crime. This is significant as ecocidal activities are often conducted by the Global North to the detriment of the Global South. Thus, recognising extra-territorial acts of widespread and long term environmental damage has the potential to recognise the global inequality produced by environmental damage. Furthermore, this also makes the changes implemented by the Directive relevant to the UK. However, the fact that it is discretionary means that it remains to be seen to what extent this impacts the prevention of widespread environmental damage outside the EU. It is foreseeable that member states will be unlikely to bring such offences of actors habitually residing within their jurisdiction to the attention of the Commission.

Overall, the Directive seeks to drive innovation and foster a harmonised sense of environmental responsibility within the EU, and to limit actors from pursuing environmental damage elsewhere, As the EU is the first international body to criminalise acts comparable to ecocide, it is to be expected that there is much more to be done. However, these are important steps in the right direction. Harmonisation within the EU will mean that environmental crime is tackled more effectively, and it is to be expected that establishing criminal liability in international cases may prove to be difficult.

The Future

What does all this mean for the future of environmental protection? Current EU environmental criminal law is weak and poorly enforced, and this Directive should make it much stronger. Yet a key question is whether criminalising environmental damage is sufficient to drive the structural changes necessary to combat the causes. This is further compounded by the fact that the ‘comparable to ecocide’ offence is a diluted one. As above, a more ecocentric approach to environmental protection would be desirable to effectively safeguard the environment.

Whilst it is agreed that this Directive will not meet this need in isolation, perhaps one of the most beneficial aspects of introducing a crime of ‘acts comparable to ecocide’ is that it expresses a strong moral decision; cementing environmental damage as among the most serious of crimes that deserves to be punished. It is widely recognised that the criminal justice system tends to underestimate the severity of white collar crimes - of which environmental crime can be included. The potential for the Directive to have extra-territorial effects demonstrates a positive step forwards for environmental criminal law to recognise the severity of the harm caused both within the territory as well as the structural injustices created by actors within the European Union causing widespread environmental damage elsewhere. The strengthening of penalties further consolidates the severity of the offence and brings hope for a future where actors causing environmental damage will be adequately punished for their crimes, thereby deterring such behaviour.

Furthermore, the preventative obligations imposed by the Directive demonstrates a positive transformation for the protection of the environment that is more than merely criminal. Overall, the focus on social awareness is indicative of a shift in environmental consciousness that is necessary to bring about meaningful change.

Conclusion

Overall, the Environmental Crimes Directive is significant progress towards the effective criminalisation of widespread and long term environmental damage in the EU. Whilst criminal law is only one facet of the structural changes needed to effectively safeguard the environment, it represents a pivotal shift in environmental consciousness. The introduction of personal liability and potential for extra-territorial offences as well as the preventative social awareness measures demonstrate an unprecedented international effort to combat environmental crime. Ultimately, the Directive’s success will depend on effective implementation, harmonisation across member states, and a continuous commitment to environmental protection. This is a historic decision by the European Parliament to criminalise environmental damage, but the work is far from over. Important next steps will include fostering a political will to pursue an ecocentric definition of environmental crime with a stronger sense of liability.

Luna Andersen Frank is a graduate from the University of Kent’s European Legal Studies program. Her primary area of research concerns the international regulation of decommissioning offshore wind turbines. She is enrolled at Utrecht University to study Public International Law with a focus on Climate and Sea Law.